INCB President Yans disqualified himself and should consider stepping down

International tensions over Uruguay’s decision to regulate the cannabis market reached new levels when Raymond Yans, president of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), accused Uruguay of negligence with regard to public health concerns, deliberately blocking dialogue attempts and having a “pirate attitude” towards the UN conventions. President Mujica reacted angrily, declaring that someone should “tell that guy to stop lying,” while Milton Romani, ambassador to the Organisation of American States (OAS), said that Yans “should consider resigning because this is not how you treat sovereign states.”

The majority vote in the Uruguayan Senate on Tuesday, December 10, gave the final green light to legally regulate the domestic cannabis market for medical, industrial and recreational use. The system for licensed cultivation and distribution through pharmacies will start in the spring under strict state controls. And as soon as president Mujica signs the bill, people will be able to grow up to six plants for personal use, and cannabis clubs can be registered to allow 15 to 45 members to grow up to 99 plants collectively. INCB president Raymond Yans said in a press release he was “surprised” that Uruguay “knowingly decided to break the universally agreed and internationally endorsed legal provisions of the treaty”.

The outcome of the Senate vote was as expected (the approval in the House of Representatives earlier this year was much more a cliff-hanger) and the fact that the INCB came out with a strong statement against it was no big surprise either. There is little doubt that the cannabis regulation schemes approved in the US states of Colorado and Washington, and now in Uruguay, fall outside of the “limits of latitude” of the UN drug control conventions. The INCB mandate includes monitoring compliance with the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the treaty in which cannabis is scheduled, so the Board can legitimately express its concern over the increasing defiance of international cannabis control requirements. As the Commentary on the 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs explains, however, the Board “has to maintain friendly relations with Governments, guided in carrying out the Conventions by a spirit of co-operation rather than by a narrow view of the letter of the law” (p. 11, § 5).

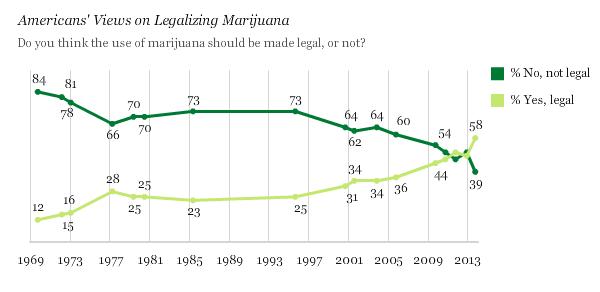

The real issue at hand is how the UN apparatus has been dealing with the reality of ongoing cannabis policy changes that appear to be irreversible, spreading out rapidly and posing fundamental challenges to the treaty system. The 2006 UNODC World Drug Report recognised that “much of the early material on cannabis is now considered inaccurate, and that a series of studies in a range of countries have exonerated cannabis of many of the charges levelled against it.” The report concludes that “[e]ither the gap between the letter and spirit of the Single Convention, so manifest with cannabis, needs to be bridged, or parties to the Convention need to discuss redefining the status of cannabis.”[1]

The real surprise this week, therefore, was to see how ill-prepared, politicised and undiplomatic the statements from both INCB and UNODC were, given that they were well aware of Uruguay’s plan and would have been conscious of the need to respond. Perhaps their awkward remarks reflect their recognition this is the beginning of an irreversible trend that they are powerless to stop. The first dominoes have fallen and there are more to come… Some US states are preparing regulation initiatives to bring to the ballot in November next year, and several more intend to do so for the 2016 presidential elections.

Offensive accusations

In the INCB press release, Yans accused the Uruguayan government and parliament of not acting in the interest of the health and safety of the population. Without any references or sources, he said that “the decision of the Uruguayan legislature fails to consider its negative impacts on health,” that “available scientific evidence … was not taken into consideration by the legislators” and that the stated aim of the legislation to reduce crime “relied on rather precarious and unsubstantiated assumptions.”

Without devoting a single word to the justification provided by the government, the detailed presentation by senator Roberto Conde or the arguments given in the nearly twelve hours of debate about the law, Yans simply gave his own unsubstantiated judgement. The legislation “will not protect young people but rather have the perverse effect of encouraging early experimentation, lowering the age of first use, and thus contributing to developmental problems and earlier onset of addiction and other disorders.”

Uruguay has developed evidence-based policies on prevention, demand reduction and risk and harm reduction for all psychoactive substances. The strong public health approach adopted by Uruguay is also showcased by its strict tobacco controls for which the country is currently being sued by Philip Morris, who are claiming billion dollar losses, and by new alcohol misuse prevention measures that will be introduced next year. Accusing this government and these legislators of negligence in the area of public health protection is unjustified and offensive. UNODC issued the same day a fairly lame statement, simply to say that they agreed with everything the INCB president said: parroting Yans was apparently the best UNODC could come up with on this crucial moment for the global drug policy debate.

The Dread Pirate Mujica

Things got worse when Yans was interviewed by EFEand accused the Uruguayan government of having a “pirate attitude” to the conventions. In a previous video interview, referring to the referenda in Colorado and Washington, he had called on these states to “stop this nonsense” – once again a disrespectful way to describe the outcome of a democratic decision making process. He hasn’t accused the US government of negligence or a “pirate attitude” yet, prompting Mujica to question a double discourse: “One for Uruguay and one for the powerful.”

To EFE, Yans also expressed his frustration on how difficult it has been to get access to the government to discuss these matters: “We have desperately tried to meet with Uruguayan authorities for two years. It is the only country in the world, with Papua New Guinea, Equatorial Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, that has refused to have a dialogue with the INCB.” Twice before, Yans had expressed the same frustration, first when a proposed INCB mission to Montevideo was cancelled and later on when “Uruguay-Guinea” decided not to send a delegation to the November 2013 INCB session.

It is not true that a high level political dialogue has not taken place. In the margins of the 2013 Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) session in March in Vienna, the Uruguayan Minister for the Presidency (“prosecretario”, equivalent to “Prime Minister”) Diego Cánepa had extensive meetings with Raymond Yans. But it is true that there was a certain reluctance on the Uruguayan side to receive Yans in Montevideo before the Parliamentary process was concluded. Yans’ attitude raised concerns that the already polarised and politicised national debate in Uruguay might be further “polluted” by his unsubstantiated personal opinions if they were presented as official UN positions. Uruguay expressed its willingness to engage in further dialogue with the Board once the legislation had been approved. By now, however, dialogue seems pointless as long as Yans remains president.

Raymond Yans is not known for his excellence in the art of diplomacy and nuance, and his controversial remarks do not represent the opinion of all thirteen INCB members. Usually no prior consultation takes place before issuing such statements presumably done by the president in name of the INCB, and as one of the members made clear that was the case again now.

UNGASS 2016

Looking at the long-term implications for international drug policy, UNODC Executive Director Yuri Fedotov said, in response to Uruguay’s decision: “It is unfortunate that, at a time when the world is engaged in an ongoing discussion on the world drug problem, a unilateral action has been taken ahead of the outcome at a special session of the UN General Assembly planned for 2016.” An intensive debate about the future direction of drug policy is ongoing, particularly in the Western Hemisphere, as Yans also recognised and “welcomed”. “Yet, such discussions should be within the framework of the drug control conventions,” he said, trying to impose limits on what states are allowed to discuss.

The reality is that as long as no country has the courage to truly challenge the dominant paradigm and to pioneer alternative policies in practice, the 2016 UNGASS will most likely result in nothing more than a slightly tweaked new “consensus” declaration. Uruguay’s Drugs Strategy for 2011-2015 mentions the need for a new drug control paradigm based on science, public health, social development and human rights, and promises to promote “a great international debate about the implementation and the results of the hegemonic drug policies in force in the last 50 years, prompting the review of the international conventions governing the matter.” According to the policy document, international agencies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNODC, the Joint UN Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), the Human Rights Council, OAS/CICAD, etc., all should be involved in the debate.

Such a process to redefine future UN drug control policy guidance is starting right now, with the CND high-level segment in March 2014 and the preparations for the 2016 UNGASS. Managing the upcoming debate constructively to reflect the diverging opinions and policies will require not only basic understanding of the art of diplomacy, but also respect for the difficult choices countries need to make in the process. In theory, the INCB could play a useful role in assisting member states to carefully manage the unavoidable future changes in the treaty system. With his blunt statements on Uruguay, however, Yans has disqualified himself, become an obstacle to constructive dialogue and should indeed consider stepping down.

This blog was written by Martin Jelsma and originally appeared on the TNI Drugs and Democracy website here.