View from the Ground – Harm reduction, drug policy and the law in the Maghreb: focus on Tunisia and Mauritania

Khalid Tinasti

Honorary Research Associate, Swansea University

July 2017

Introduction:

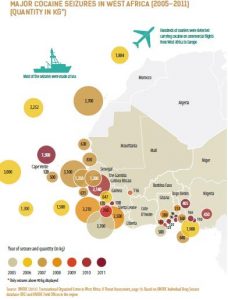

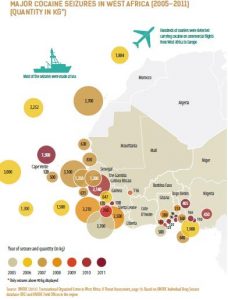

The Maghreb countries – Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia – while seldom discussed, are crucial to global debates on drug control policies. These countries are at the heart of drug trafficking routes for various substances, from Latin America to Europe, from the Middle East to Europe, and from West Africa to North America. The region is also home to the largest producers of cannabis, as well as amphetamine type stimulants (ATS). Illicit drugs are prohibited and drug laws are harsh if not efficient – Mauritania retains death penalty for drug-related offences.

The Maghreb (in green), copyright epidop.com

This blog will focus on two of these countries, Tunisia and Mauritania, who share common religious, ethnic groups, cultural and socio-economic realities, but face clearly different challenges related to illicit drugs.[i] The two countries nevertheless face a drug trafficking framework which is unparalleled. In fact, the Maghreb and its neighbouring Sahel region represent large desert areas, sparsely populated, with porous borders and the existence of terrorist and other separatist groups. These parameters, combined with failed states and inadequate drug control policies, make drug trafficking thrive. This blog attempts – through available data and literature – to analyse the drug situation currently in both countries, review their drug control laws, and evaluate the outcomes of their implementation. The piece also narrates the current efforts to reform the drug law by the Tunisian government.

The current situation:

There are an estimated 140,000 people who use drugs (PWUD) in Tunisia,[1] with around 10,000 people injecting drugs.[2] Other sources report up to 400.000 PWUD in the country.[3] In 2015, 21.44% of new HIV infections were among people who inject drugs.[4] Moreover, HIV prevalence among this same population has increased from 3% in 2011 to 4% in 2014, while it is of 0,1% in the general population.[5] This increase takes place in the absence of a national strategy of harm reduction. There are no opioid substitution programmes, and the distribution of syringes is mainly undertaken by non-governmental organizations. In 2013, the 48.000 syringes distributed in the country were by the ATIOST, the ATUPRET and the ATL-MST.[6] The prevalence of hepatitis C in the same population is 29%.[ii]

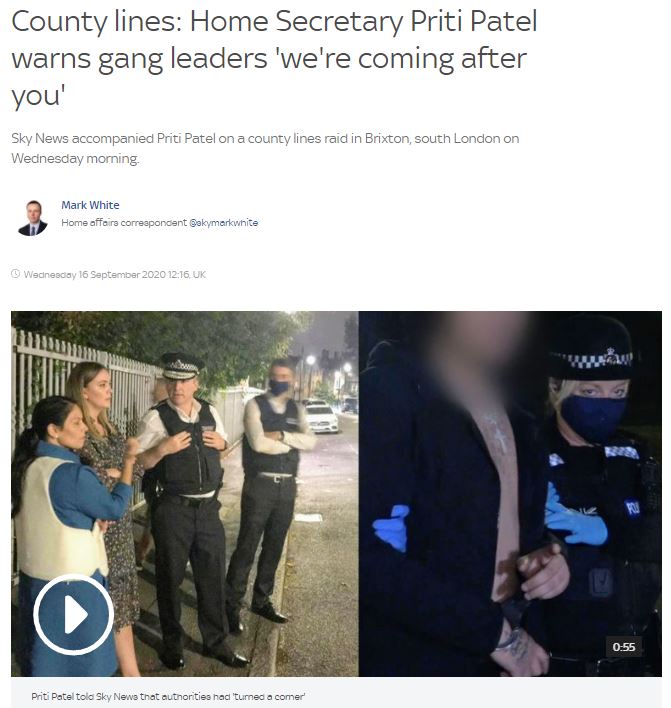

Drug control policies are steered through law 52 adopted in February 1992 – referred to as law 92-52. The law, which sentences prison terms even for simple use or consumption, has resulted in an unprecedented prison overcrowding, mainly targeting young males incarcerated on cannabis use charges. Out of the 25.000 inmates in the country prisons, 8.000 are incarcerated for drug offences, of which it is estimated that 9 out of 10 are there for simple possession or personal use,1 the law allowing for urine tests in prisons and in the community to prove the consumption. In 2015, 7.451 people were arrested and prosecuted for drug offences, of which about 70% were related to cannabis possession or consumption.[7] A year later, 8.984 people were arrested on the same charges, with 6.212 of them aged 18 to 30 years old.[8]

In Mauritania, data on the prevalence of drug use is unavailable. Similarly, the prevalence of HIV among the general population reaching 0,6%, the prevalence among people who inject or use drugs is unavailable. More worryingly, the National Committee to fight AIDS does not recognize PWID as a key population most at risk of acquiring HIV.[9], The non-inclusion of PWUD as a key population deters a discussion on evidence-based interventions to respond to AIDS, including prevention, harm reduction services and treatment.

Copyright West Africa Commission on Drugs, 2014

Rather, the debate on drugs focuses heavily on trafficking, with Mauritanian authorities, media and other stakeholders considering that the country is only a transit country. This vision of a country where illicit drugs transit – through the routes of Senegal, Mali, Algeria, Niger, Morocco or the Canary Islands – and where there is no local consumption is emphasized by the geographic position of Mauritania, its limited population (4 million inhabitants), and a large, desert and difficult to control territory. Whether such assertion is true or not – it remains difficult to define in the lack of data on illicit drug use – the country rightly faces challenges related to the smuggling and trafficking of drugs, intertwined with terrorist groups’ financing and their unlawful intrusion in the Mauritanian territory. Drug-related cases often make the headlines in Mauritanian media, due to the large seizures of illicit drugs by customs and law enforcement agents, including cases where relatives of former Presidents or former Presidents themselves are cited.[10][11] The nature of the implication of political authorities in drug trafficking remains anecdotal since it is not proven. Nevertheless, the characteristics of drug trafficking depends on many parameters that are specific to Mauritania and the Sahel region. As stated earlier, the country has a large desert territory that is difficult to control. Moreover, trafficking relies on ethnic groups, their inter-relationships and their control of their territories that transcend the Sahel borders.[12]

Drug seizure in northern Mauritania by the Gendarmerie (military law enforcement). Copyright Sahara Medias

Very limited data shows that there is a small cannabis production in the south of the country near the Senegal River, while cocaine is imported from Latin America and heroin from Asia through Nigeria or other West African countries.[13] Trafficking of illicit drugs includes alcohol, which is a banned substance in Mauritania. Moreover, Mauritania’s authorities address money laundering as the banking system is sensitive to drug profits laundering, mainly due to the important volume of foreign currency circulating from tradespeople and other economic emigrants working mainly in the Gulf countries.

The laws and policies for drug use and trafficking:

Tunisia, country of the Jasmine revolution and youth-driven democratization, has the harshest law in terms of repression of drug use and possession for personal use. Mauritania, on the other hand, is the only Maghreb country sentencing drug traffickers and growers/producers to death penalty.

The Tunisian law – to be explored in more detail below – punishes individuals who consume or possess a narcotic or psychotropic drug with imprisonment of one to five years and with a monetary fine between 400 and 1.200 USD (1.000 to 3.000 Tunisian Dinars). It also punishes the attempt to consume or possess drugs with the same sanction. Therefore, the Tunisian law punishes the possession for the purpose of consumption and for the actual consumption even if there is no possession involved. The court may as well force the convicted offender to undergo detoxification for a period set by a medical doctor at a public hospital. If the detoxification is refused, a permit can be issued by the president of the court forcing the offender to undergo this treatment in a compulsory manner.[14] The most problematic provision of the law, until its partial reform in April 2017 (see following section), was article 12 of the law, providing that judges cannot take into account mitigating factors, and have to pronounce a prison sentence for drug use offences. This was problematic as the law 52 was the only one in the Tunisian criminal code to deprive judges of their free choice and of sentencing proportionally to the offences. Under the terms of the law as well, traffickers and growers of narcotics are sentenced to prison terms from 6 to 10 years, while those importing or exporting drugs face a minimum of ten years of incarceration, up to a life sentence.

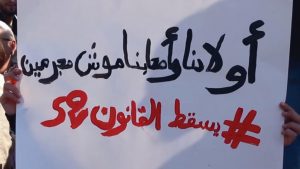

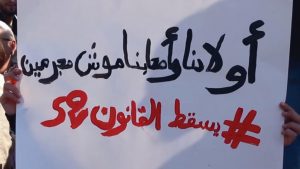

“Our kids and friends are not criminals #end law 52”[iii]

In Mauritania, the law responds to drug use and possession for personal use by a prison term of a maximum of two years and a monetary fine between 140 and 280 USD (50.000 to 100.000 Mauritanian Ouguiya). Prosecutors also have the obligation to inform health authorities about the arrest of people who use drugs. The health authorities investigate the health conditions and family conditions of the arrested individual, and prescribe mandatory detoxification. Producers and growers of illicit drugs face 15 to 30 years in prison, the same penalty as drug traffickers. This punishment, in case of recidivists, becomes a sentence to the capital punishment. Finally, laundering illicit drugs’ profits is punished by a prison term between 10 to 40 years.[15]

It is also important to note that both laws have been amended and adopted following the adoption of the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances in 1988 and right before the adoption of the Arab Convention against Illicit Use of and Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances in 1994. The articles of both countries’ laws and the lack of proportionality vis-à-vis the real severity of the offences represent an example of the interpretation countries make of the international drug conventions, and the impact these conventions have on people’s lives when implemented on the ground, far from the debates of diplomats drafting and negotiating them in multilateral forums.

What reform for the Tunisian drug law?

In Tunisia, the excessive number of young people arrested under the provisions of law 92-52 started a heated debate on the need for its reform. This debate has been deepened through the use of the law provisions to arrest young Jasmine revolutionaries, and by their own capacity to stand for their rights in the post-Revolution era.[16] Movements such as the Sajin52 (prisoner 52) emerged and denounced the law. In his 2014 presidential campaign, the current head of state Béji Caïd Essebsi promised a reform of the law and denounced the use of prison terms for first-time drug use. In December 2015, his government approved a new narcotics bill to amend law 52, and introduce the following provisions: i) the establishment of a national drug observatory to collect data; ii) the establishment of treatment centres, including the introduction of substitution therapy; iii) the diversion of first and second-time offenders, arrested for use, to social services (third-time offenders will serve the same terms as the current law provides, between one and five years); and iv) the possibility of judges to decide on the most appropriate sentences.[17]

Infographic by the movement “Al habes lé” (no incarceration) calling to reform law 52

The latter, targeted at article 12 of law 92-52, has been amended in April 2017 when Parliament gave judges the right to apply Article 53 of the Criminal Code to reduce penalties, not only for consumption, detention and consumer intent (Article 4 of law 52) but also for attending consumption spaces (Article 8 of Law 52).[18]

The process leading to this partial amendment started with the submission to Parliament of bill 79 amending law 52. With the bill not finding a majority necessary for passage into law for more than 12 months, President Essebsi decided in January 2017 to use his executive powers to freeze all the arrests related to Law 92-52, and urged Parliament to find a consensus and vote for the reform. A month later, the President convened a meeting of the National Security Council, which decided to revise the criteria for granting special grace to people charged with drug use or possession, and to have the Grace Committee meet once a month to overturn the judges’ decisions on arrests. The National Security Council also repealed partially law 92-52, and specifically its article 12 leading to the reform of April 2017 by Parliament, giving judges the capacity to take into account mitigating factors.

In the current economic, social and security framework in Tunisia, where tensions among society are numerous – from the declining standards of living of the population, the decline of the industrial, tourism and service sectors, as well as the security and fight against terrorism – the calendar of the adoption of bill 79 in Parliament remains unclear.

Conclusion:

The debate on drug policies in the Maghreb, when it occurs, is usually focused on Morocco, the largest producer of cannabis in the world, and one of the main suppliers of the European Union due to its geographic proximity with Spain. With the deterioration of the security situation in the Sahel and the rise of terrorist risks, along with some evidence that terrorist groups are either involved in trafficking, protect traffickers or benefit from trafficking revenues,[19] combined with the disintegration of the state apparatus in the fifth Maghreb country, Libya, is also beginning to attract some interest.

Nevertheless, as discussed here, other states within the region are increasingly worthy of attention with debate around drug policy emerging for a complex range of internal, societal and social peace reasons.

Tunisia is currently being driven to reform its policies due to the population’s pressure, while this debate does not exist in Mauritania. However, while differences exist on this point,, the two countries seem to share a common lack of understanding of drug policies, providing similar legal responses to people who use drugs (PWUD), to small players in the illegal drug market (small dealers, farmers and other couriers), and to large-scale traffickers and terrorist groups suspected of trafficking illicit drugs to fund their terror actions. Such policies, intended to deter drugs’ presence in society, are failing to achieve their objectives and are extremely costly to society, to the criminal justice and health systems.

While it remains unclear when the Tunisian drug policy reform will take place, it provides the brightest prospect of reform in the Maghreb, as bill 79 will bring along the first policies based on evidence, and provide space for scientific monitoring to inform and fill gaps in the future. The adoption of this bill, its successful implementation and flexibility, as well as its tight monitoring is all highly important not only for the Tunisian society but the whole Maghreb.

[I] This is the second and last blog on drug policy in the Maghreb. The first blog was published in October 2016 and titled “View from the Ground – Harm reduction, drug policy and the law in the Maghreb: focus on Morocco and Algeria”.

[ii] In Mauritania, HIV key populations are female sex workers and their clients, women and youth, inmates, people living with STIs, truckers, sailors and fishermen.

[iii]Protest against law 52 in front of the Assembly of the Representatives of the People (Parliament) on 28 December 2015. Copyright Nawaat

[2] Tunisie Numérique. 10 000 toxicomanes usagers de drogue intraveineuse en Tunisie. Turess; April 2012. Available from: http://www.turess.com/fr/numerique/119208 (accessed 10 July 2017)

[5] UNAIDS. Key Populations Atlas: Tunisia- People who inject drugs: HIV Prevalence 2014. UNAIDS; 2014. Available from: http://www.aidsinfoonline.org/kpatlas/#/home (accessed 10 July 2017)

[6] National HIV/AIDS Programme of Tunisia. Rapport d’activités sur la riposte au sida 2012-2013. UNAIDS; 2014.

[7] Human Rights Watch. « Tout ça pour un joint » La loi répressive sur la drogue en Tunisie et comment la réformer. Tunis; December 2015. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/tunisia0216fr_sumandrecs_.pdf (accessed 11 July 2017)

[9] Comité national de lutte contre le Sida. Rapport d’activité sur la réponse au sida en Mauritanie 2014. Nouakchott; March 2014. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/MRT_narrative_report_2014.pdf (accessed 10 July 2017)

[10] Berghezan, G. Panorama du trafic de cocaïne en Afrique de l’Ouest. Group for Research and Information on Peace and Security: Brussels; June 2012.

[11] Attar, A. Mauritanie : fin de parcours pour Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz ?. Afrik.com; February 2013. Available from: http://www.afrik.com/mauritanie-fin-de-parcours-pour-mohamed-ould-abdel-aziz (accessed 10 July 2017)

[12] Simon, J. « Le Sahel comme espace de transit des stupéfiants. Acteurs et conséquences politiques ». Hérodote, 142 (3); 2011: pp. 125-142.

[13] Dialogues, propositions, histoires. « La situation des drogues en Mauritanie ». DPH: Paris; citing the Observatoire géopolitique des drogues; November 1994. Available from: http://base.d-p-h.info/fr/fiches/premierdph/fiche-premierdph-2016.html (accessed 11 July 2017)

[14] Official Journal of the Tunisian Republic No. 33 of 1992. Law No. 92-52 of 18 May 1992 on Narcotic drugs. Tunis; 1992.

[15] République Islamique de Mauritanie. Loi No. 93-37 relative à la répression de la production, du trafic et de l’usage illicite des stupéfiants et substances Psychotropes. Nouakchott ; July 1993.

[16] Tinasti, K. Are cannabis laws used for political repression in the Arab Spring countries?. Addiction, 110 (12); 2015: p. 2037.

[17] Tunisian government. Projet de loi N 79 de l’année 2015 relatif aux stupéfiants. Tunis; 2015.

[18] Huffpost Tunisie. Tunisie-La loi 52 a été amendée: “Une étape considérable franchie” se félicite l’avocat Ghazi Mrabet. Huffpostmaghreb.com; April 2017. Available from: http://www.huffpostmaghreb.com/2017/04/25/tunisie-loi-52-stupefiant_n_16231606.html (accessed 12 July 2017)

[19] UNODC. World Drug Report 2017, booklet 5. Vienna; June 2017