By Ellie Harding, MA candidate in Applied Criminal Justice and Criminology, Swansea University

‘We are cutting the head off the snake and taking down the kingpins behind these deadly supply lines…Drug abuse and addiction ruins communities, devastates lives and tears families apart.’

So announced Priti Patel in her speech to the annual Conservative Party conference earlier this month. Strong words from the Home Secretary, and certainly a standpoint that will strike fear in the electorate. This is arguably what the speech was intended to do. To generate fear and concern in the populace, rather than inform a discussion about a complex and multifaceted topic of drugs, crime and society.

A ‘moral panic’ is a criminological concept which suggests that stylised and stereotypical media reporting of a ‘threat’ to society results in a panicked response from the public, often leading to knee-jerk policy responses. In 1998, Kenneth Thompson identified several essential elements of a moral panic. These include (a) something is defined as a threat, (b) the threat is portrayed in the media, (c) the threat emerges rapidly in the public consciousness and (d) the threat provokes a response from the authorities.

Drugs as a moral panic in the UK is not a new phenomenon, and Priti Patel’s framing of the issue of county lines is certainly in keeping with that troubling tradition. As most audiences do not experience crime first-hand, they instead develop their understanding of criminality through media depictions. Since 2017, county lines drug trafficking has increased as has high profile media attention of the issue. This raises the concern of whether the representation of county lines in the British media is fuelling fear rather informing debate, and whether it meets the threshold of a ‘moral panic’.

Existing research around this topic lacked depth, therefore I conducted a study to examine whether media portrayal of county lines in the UK met the definition of a moral panic. To test this question, this research reviewed 132 online news articles from five major media outlets (BBC, Daily Mail, The Guardian, ITV and Sky News) and studied the language and imagery each used to report county lines. It examined how different players in the situation are represented – young people, ‘gang leaders’, police – and drew conclusions about the impact of these characterisations on public understanding of county lines. The results of the analysis concluded that the representation of county lines can comfortably be described as a moral panic.

The research documented the common use of terms such as ‘exploited’ (used 210 times) or ‘vulnerable’ (used 192 times) to describe the young people involved in the county lines drug trade, paired with stylised images of drugs (used 38 times). It found that the articles were empathetic to these individuals, who were often referred to as ‘victims’ (used 58 times) rather than criminals, with a focus on their vulnerabilities and associated risks. For example, one article described the children involved in county lines as “the disposable foot soldiers of crime”.

On the other hand, dehumanising descriptions were evident of those described as controlling or directing these trafficking operations. It was common to find the use of gang terminology such as “professional gangsters exploiting vulnerable minors”, despite the societal stigma associated with such language. The articles’ language often focused on the control and coercion associated with county lines (combined use of 64 mentions). This representation was paired with the use of mugshots (being featured 59 times), giving the audience a voyeuristic look into the criminal consequences of county lines. The impact of county lines was typically depicted using violence and weapons (mentioned 139 times with nine images of weapons), overall adding to public fear.

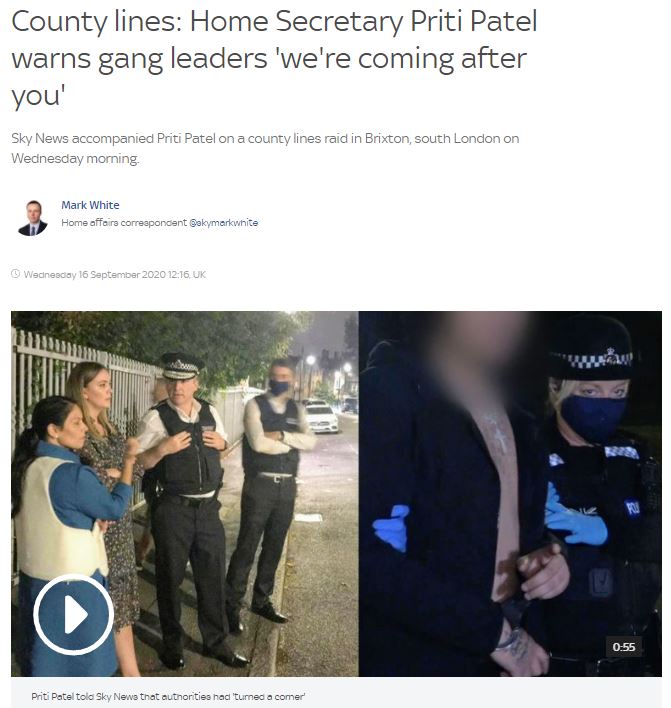

Articles also focused on the response from the government and law enforcement. This included language such as ‘crackdown’ (used 35 times) and images of the police (featured 60 times). Articles emphasised that policing county lines is a priority for government and law enforcement, using statistics of arrest rates and seizures of drugs and money to prove to the public the success of the police. This, combined with the repeated use of images of the police reinforces to the public that county lines is a threat to society, contributing to a sense of moral panic.

The research found the Daily Mail relied particularly heavily on information from the Home Office when reporting on the issue. Many of its articles focused on Priti Patel’s response to county lines and the new ‘Beating Crime Plan’ from a personal perspective. “I will not tolerate county lines drugs gangs terrorising our communities and exploiting young people, which is why I have made tackling this threat a priority”. The Home Secretary was featured in Daily Mail reporting far more often than in any of the other news sources examined.

The research also examined the extent to which the media offered support and protection to the vulnerable individuals involved in county lines (both the children used as drug couriers and the adult victims whose homes may be ‘cuckooed’ and taken over for drug dealing activities). Only two out of the five media outlets (BBC and ITV) consistently used their platforms to promote support and protection services. This included profiling organisations that offer services and other ways to promote the support and protection of the vulnerable individuals.

The overall conclusion from this research suggested that the manner in which county lines is portrayed in the British media meets the definition of a moral panic. The study indicates that the media are more focused on selling a story using a ‘scary’ narrative rather than supporting vulnerable people involved in county lines. This moral panic arguably gets in the way of the more important discussions about the context of county lines, drug markets and criminalisation.

The research found that the contributing factors driving county lines (although alluded to) need further emphasis from the media, as this would allow the public to better understand the issue and potentially have a more empathetic response. For example, the socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds of many of the individuals involved in county lines needs to be further featured in media news outlets. This includes more focus on issues such as poverty, lack of employment opportunities and the impacts of austerity, which are often drivers of county lines involvement. Similarly, the increasing rates of school exclusions (especially racially motivated ones) need to be addressed by governing bodies as well as the media, as this highlights the vulnerability of children who are then exploited by county lines organisations.

Regardless of reporting, while there is demand there will be supply of drugs. The counterproductive ‘war on drugs’ therefore needs to be addressed, but the moral panic surrounding county lines gets in the way of discussing bigger policy issues. The ‘war on drugs’ is driven through law enforcement, however these efforts against county lines often result in displacement, whereby “one county lines closes another quickly opens”. Therefore, the media reporting of county lines may not highlight the true extent of the problem, or the limitations of a law enforcement centred approach.

Within the county lines discourse there is also little discussion of the negative short and long-term impacts of the early introduction of the young people involved into the criminal justice system. Prevention/education and harm reduction programmes are not represented, and the issues of decriminalisation or legalisation are often the subject of their own moral panic.

Overall, not only the media but society as a whole need to support and protect the vulnerable individuals involved in county lines, rather than the moral panic style reporting which is more focused on selling stories rather than the potentially damaging effect of their reporting styles.