Emily Crick, Bristol, UK

Amidst current debates about the inadequacies and damaging ‘unintended consequences’ of policies and programmes that privilege harsh law enforcement and punishment, what has become known as the ‘war on drugs’, it is instructive to reflect upon the history of this long dominant policy approach. Here Emily Crick, PhD student at Bristol University and GDPO Research Associate draws on her doctoral research to discuss US President Ronald Reagan’s engagement with the issue in the 1980s.

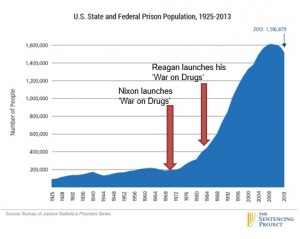

US President Richard Nixon is often credited with launching the ‘War on Drugs’, but my research suggests that in fact it was the Reagan administration, with support from Nancy Reagan, who really shaped and militarised the ‘War on Drugs’ as we know it now. The Reagan era introduced and propagated across the world a virulently prohibitionist and highly militarised form of international drug control.

Under the Reagan administration:

- the military was encouraged to get involved in drug law enforcement

- mandatory minimum sentences were increased for drug offences – including the death penalty for ‘drug kingpins’

- random drug testing was normalised for US federal employees

- asset seizure laws were strengthened in America and then enshrined into international drug control policy through the 1988 UN Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances

- the policy of ‘certification’ was introduced to compel countries to commit to US drug control initiatives

Nancy Reagan also contributed to the staunchly prohibitionist atmosphere with her ‘Just Say No’ campaign that reduced drug use to a simple question of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and shifted funding away from drug treatment towards abstinence-based programmes.

Under the Reagan administration the ‘war on drugs’ was intensified domestically and internationally. Within the US, there were a number of legal changes that created a much harsher environment for those involved in the drug trade and contributed to a huge increase in prison populations (see fig.1) .

- The Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 eliminated parole for most federal prisoners.

- The Comprehensive Crime Control Act (1984) enshrined ‘civil forfeiture’ into law that allowed assets to be confiscated even before charges had been brought. It also allowed for enforcement agencies, both federal and local, to share the proceeds.

- The Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) introduced increased mandatory minimum sentences for drug offences

- Executive Order 12564 (1986) established random drug testing for Federal employees

- Drug Abuse Act of 1988 introduced the death penalty for ‘drug king pins’

Fig. 1.

Some opposed these policies at the time. A Washington Post editorial argued that the best way to deal with ‘the drug problem’ was education and treatment and that federal workplace testing, military involvement in civilian law enforcement and mandatory minimum sentences undermined civil liberties. The stringent asset forfeiture and seizure laws, many argued, undermined the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution that prevented US citizens from being searched without ‘probable cause’.

At the same time as the criminal code was being tightened up, Nancy Reagan was promoting her ‘Just Say No’. This involved an overly simplistic message that didn’t take into account the multitude of reasons why people use drugs problematically. However, the ‘Just Say No’ campaign joined with the Parent Power movement of the 1970s to create a strong anti-drug message that contributed to the zero-tolerance, abstinence-based perspective on drugs. In 1988 Nancy attempted to internationalise her message when she became the first US First Lady to address the UN General Assembly. She gave a speech promoting the ‘Just Say No’ campaign and calling for a bigger focus on demand-control.

Internationally, drug trafficking was being seen as a threat as well. During the 1980’s a new threat was articulated – the narco-terrorist. It was first used by Peruvian president Fernando Belaunde Terry in 1983 in response to the rise of the Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path. Both Reagan and later Bush Snr. used the ‘narco-terror’ threat as cover for Anti-Sandinista policies in Central America.

In 1986, Ronald Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive 221 (NSDD-221) that set out how the military and intelligence communities should participate in the ‘War on Drugs’. It stated that, “Whilst the domestic effects of drugs are a serious societal problem for the United States … the national security threat posed by the drug trade is particularly serious outside US borders. Of primary concern are those nations with a flourishing narcotics industry, where a combination of international criminal organizations, rural insurgents, and urban terrorists can undermine the stability of local the government; corrupt efforts to curb drug production; and distort the public perception of the narcotics issue in such a way that it becomes part of the anti-US or anti-western debate.” NSDD-221 not only linked domestic drug use and international drug trafficking together as threats to the US, but also situated global drug control within the geo-political context of the Cold War. It named three countries – Bulgaria, Cuba and Nicaragua (all Soviet allies) – as countries that were using drug trafficking for “financial and political reasons” to undermine the US. This was despite the fact that these countries were low down on the list of nations that had a well-developed illicit drug trade.

Also in 1986, the Reagan’s made a series of highly emotive statements on drugs. In May 1986 Ronald Reagan claimed that “… illegal drugs were every bit as much of a threat to the United States as enemy planes and missiles”. And in September of that year he argued that, “Drugs are menacing our society. They’re threatening our values and undercutting our institutions. They’re killing our children.”

Nancy Reagan, in a speech with her husband from the White House in 1986, stated, “Today there’s a drug and alcohol abuse epidemic in this country, and no one is safe from it – not you, not me, and certainly not our children, because this epidemic has their names written on it….. It concerns all of us because of the way it tears at our lives and because it’s aimed at destroying the brightness and life of the sons and daughters of the United States.”

When announcing NSDD-221, Vice President George Bush went further are maintained that “when you buy drugs you can also very well be subsidizing terrorist activities overseas.” These statements emphasise the Reagan administration’s view that drugs, drugs users and drug traffickers were a threat to both US national security and US societal security. By continuously linking together the threat of drugs and drug trafficking with the protection of the ‘family’ and ‘our children’, this created a powerful image.

Since 1981, when Reagan amended the Posse Comitatus Act that had prevented that military from participating in civil law enforcement, and therefore counter-narcotics operations, there had been a debate about the role the military should play in the ‘War on Drugs: should they simply contribute equipment, or should they carry out active participation including having the power of arrest?

There were long-standing tensions between the Pentagon, the Reagan administration and Congress about the role of the military in drug law enforcement, but nevertheless the militarisation of the ‘War on Drugs’ had begun. When in 1985 the House of Representatives proposed giving the military powers of arrest and seizure for the second time, Defense Secretary Weinberger strongly opposed this arguing that, “…reliance on military forces to accomplish civilian tasks is detrimental to both military readiness and the democratic process…. We strongly oppose the extension of civilian police powers to our military forces.” And when, in 1988, the issue was raised again by Congress, Weinberger, by this point no longer Secretary of Defense, came out against the proposals even more forcefully, stating, “Calling for the use of the government’s full military resources to put a stop to the drug trade makes for hot exciting rhetoric. But responding to those calls would make for terrible national security policy, poor politics and guaranteed failure in the campaign against drugs.”

This advice was completely disregarded. And in 1989 when, shortly after coming to power, the new President Bush Snr. invaded Panama to arrest General Noriega – a one-time ally of the US – on drugs charges, it was agreed that restrictions on the military’s powers of arrest and seizure only applied within the US.

Whilst the military were wary of committing themselves to involvement in the ‘war on drugs’, the intelligence agencies were much keener to get involved. Nixon had ordered the CIA to participate in fighting drug traffickers in 1972 and Reagan mandated that the FBI get on-board in 1981. The CIA analysed the threats caused by the illicit drug trade in the 1980s and produced a National Intelligence Estimate in 1985 that stated, “drug trafficking that can threaten the integrity of other democratic nations…. This Estimate does underscore the manner and degree to which drug trafficking can undermine countries important to the United States, and it defines the interrelationship between drug trafficking and other issues significant to our national interest such as insurgency and terrorism.” National Security Decision Directive -221 was based on this National Intelligence Estimate.

Shortly after NSDD-221 was signed, the US carried out Operation Blast Furnace in Bolivia. The US sent six Black Hawk helicopters and 160 military personnel into Bolivia to eliminate cocaine processing labs. Even at the time, they recognised that this operation would only have a short-term effect on cocaine prices and availability. In the end, though, the operation focussed mostly on eradicating coca rather than closing down the labs and this caused a lot of animosity amongst the locals.

In November 1986 the US called together their ambassadors from drug producing and transit countries – as well as some allies in the war on drugs – and told them to impress upon their host nations how much importance the US attaches to fighting the drug war. Another aspect of the internationalisation of the US ‘war on drugs’ was the policy of ‘certification’. This policy was created though the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act and 1988 amendment to The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. The amendment stated that, “International narcotics trafficking poses an unparalleled transnational threat in today’s world, and its suppression is among the most important foreign policy objectives of the United States….” In order to make producer and transit countries conform, certification required the US president to certify that specified drug production and transit nations were “co-operating fully” with the United States in a range of stipulated counter-narcotics measures. If countries were deemed not to be co-operating, they could face the suspension of US aid and US opposition to loans from regional and multilateral development banks such as the World Bank and the IMF.

In the late 1980s, it was agreed that there was a need for a new UN drug convention – the 1988 UN Convention Against Illicit Trafficking in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. The US was closely involved in drafting this convention. It was argued that the country had considerable “experience in developing effective law enforcement tools” against traffickers. And therefore incorporated into the treaty US-style law enforcement measures such as asset seizures, “special investigative techniques such as electronic surveillance … and undercover operations…” The US also used the 1988 Convention legitimise the certification process: it called for each country to state how far they had “met the goals and objectives of the [1988 Convention]”. The 1988 Convention can be seen as the internationalisation of yet more flawed US approaches to the drugs trade and organised crime.

Reagan built upon the ‘War on Drugs’ discourse that had been created by Nixon but he went much further. Reagan militarised the ‘War on Drugs’ and then internationalised these aggressively prohibitionist policies. Later US presidents only increased this direction. This can be seen with Clinton’s Plan Colombia and George Bush Jnr.’s merging of the War on Terror and the War on Drugs. The US has also influenced the direction of international drug control through policies enshrined in the 1988 UN Convention and through joint counter-narcotics operations, massive funding and support for training programmes. The highly militarised and punitive ‘war on drugs’ that we continue to see today had begun.

This blog has been adapted from a presentation given at the UCL Mexico Summit on June 13th 2016.