by Ross Eventon

Bogota, Colombia

After decades of studies demonstrating the inefficiency and the harmful effects, the environmental damage and the health problems, the Colombian government announced in June that it would be stopping aerial fumigation of illicit crops using the herbicide glyphosate. It has been an interesting and somewhat depressing experience to read the international commentary and analysis published since then. “The decision to suspend the fumigation program suggests that president Santos understands the necessity of promoting reforms not just at a global level, but also at home,” one analyst told the Spanish press in a typical formulation that manages to present three key misconceptions in one sentence: i) The decision was made by the Ministry of Health, invoking the precautionary principle which the constitutional court determined to be applicable following a World Health Organisation statement that glyphosate is carcinogenic to humans. The President had his hand forced: his only move was to put it to a vote and to recommend the resolution to suspend be passed. ii) The fumigation programme has not been suspended – it continues until October and then it is fumigation with glyphosate that will stop. iii) The decision doesn’t demonstrate a commitment to change. In fact the available evidence suggests the government is committed to the same policies, except slightly modified – possibly using a new herbicide, maybe switching to forced manual eradication instead.

The Man, The Myth

President Juan Manuel Santos, one analysis claimed recently, is “a champion of drug policy reform in the international arena”. The Santos administration’s policy of chemical warfare against its own population, to be continued openly through a ‘transition period’ lasting until October, has not, it seems, undercut a reputation achieved by force of rhetoric alone. The commitment to an economic model that worsens the issues at the core of illicit crop cultivation has also been deemed irrelevant by the international press and the drug policy community. In the drug policy literature it is repeated ad nauseam that general economic development is crucial if illicit cultivation is to be reduced, but, to my knowledge, not a single drug policy expert quoted in the international press drew the link between the Colombia-US Free Trade Agreement signed in 2011 and the spike in coca cultivation between 2013 and 2014. The predictions made by international NGOs before the signing of the FTA appear to have been correct: subsidised goods from the US are putting the squeeze on the incomes of some of the poorest people in the country, driving migration and illicit cultivation. The passing of the most important pro-narcotics policy in recent Colombia’s recent history and the government’s fanatical pursuit of an economic policy that exacerbates the problems at the core of cultivation does not, according the prevalent view among experts, undermine claims of concern with ‘counter-narcotics’. In the same vein, a man in a white coat who stabs someone while offering them an aspirin is no doubt committed to medicine, but is perhaps “ill-informed”, “misguided”, and should reassess his “failing” methods (the analogous debate for commentators would be whether aspirin should be replaced with codeine? 50mg or 100mg?).

The disconnect between reality and reporting goes beyond drugs. As Defense Minister during the previous administration, Santos oversaw a rise in cases in which the military murdered innocent civilians in exchange for cash and promotions, and has since tried to ensure impunity for those responsible by passing reforms that would move cases to the notoriously biased military courts. Mass displacements have increased over the course of his presidency, and his administration passed the internationally celebrated Land Restitution Law, a policy so cynical it staggers belief, one that played on the hopes of millions of displaced families to achieve greater security for foreign investments and sent dozens of unprotected land restitution leaders to the slaughter in the process. Santos has deepened the exclusionary economic policies of his predecessor, but this “modern and decent” politician, quoting the UK Guardian, has done all this with a professionalism that breaks with the crass, blunt style of Uribe, and for this he has been showered with praise and hagiographies in the international press.

The past few months have provided typical examples of the duplicity. In May, the newsletter of the Colombian National Police published an article by Santos in which he claimed, contrary to the evidence, that “the country has been relatively successful” in the fight against narco-trafficking. He went on to ask, “What can we do going forward in our country?” and he answered: “In the first place – and in this there should be no doubt – we will continue directly combatting, with all the power of our police forces and the support of our military forces, the criminal organisations that profit from narco-trafficking and its environment of illegality.” Mentioned also was the now familiar talk of a need to improve the situation for poor campesinos – a cruel comment, given the economic policies being pursued – but reading the piece one would not assume that drug policy in Colombia had been too far off-base. That same month Santos spoke at the International Conference of Drug Control, held in the coastal city of Cartagena. There, in front of law enforcement officials from around the world, he declared the necessity to move away from the War on Drugs policies – which have relied overwhelmingly on the police and military forces – and acknowledged that under the current approach “we have to recognise that we haven’t won.” This rhetorical flexibility, coupled with the predilection of commentators to value words over actions, has bought the political space for draconian policies at home.

Anatomy of a Failed Policy

Inside the country, commentary has been far more critical and informed. Compare, for example, the lazy and ubiquitous references in the international press to fumigation as a “failed” counter-narcotics policy, a demonstration of the “lunacy” of US and Colombian policy makers, with the words of the respected local journalist and author, Alfred Bravo, published a few weeks ago in El Espectador, Colombia’s second largest daily:

“The aspersion – as they refer to it in order to disguise the aggression – is also a sister weapon of paramilitarism, one which seeks to displace farmers and settlers. The thesis of “taking the water from the fish” – to remove the support of the campesinos from the guerilla – is the fundamental strategy of a war against an insurrection. The paramilitaries did it with massacres. Fumigation does it by ruining crops, not just coca but also the produce that allow farmers to feed themselves: yuca, plantain, rice. Moreover, areas that have nothing to do with coca are also devastated as the poison ‘drifts’, which is to say, it is dispersed by the wind. Viewed correctly, fumigation is a new means to remove farmers from colonised areas they have settled in search of a livelihood; Catatumbo, Meta, Guaviare, Magdalena Medio, Perijá, San Lucas, Urabá, bajo Cauca. Terrorised, the settlers have been expelled from their original lands. … What the paramilitaries do on one side, fumigation completes on the other.”

These comments go a way in explaining not just the survival but the expansion of what is almost universally referred to as a failing, even counter-productive policy. On grounds of logic, the use of fumigation, and Washington’s attempts to apply it elsewhere, suggests it produces favourable outcomes. It is not difficult to discern what they might be. The expected, consistent results of forced crop eradication are the same around the world: displacement and impoverishment of the local population. In 1992, at the beginning of a new US-backed fumigation drive, the head of the Colombian Police explained that fumigation had been effective because by creating economic hardship it “obligated farmers to return to their place of origin”. And he went on to explicitly frame fumigation in counter-insurgency terms: “Up to now 1040 hectares have been fumigated [which means] the guerrilla groups operating in the zone have therefore not received a little over 5 billion pesos.” The Colombian counter-insurgency strategy backed by Washington is predicated on “the premise that those living in conflict areas are part of the enemy, simply because of where they live,” quoting Amnesty. Such a useful policy is not going to be sacrificed simply because it fails to produce its publicly stated goals. And with the actual aims in mind, the fact that fumigation happens to be harmful and indiscriminate is not a problem but a virtue.

There are other benefits. Across the country, where the chemical’s task has been successfully carried out, mining and agrobusiness operations have moved in to take over of the land and begin operations. For these groups, and for the wealthy individuals who are able to purchase land at rock-bottom prices, fumigation has not been a failure. Nor has it failed for DynCorp, the private military services company contracted to carry out the policy. Nor do US officials consider it a failure. Plan Colombia is, according to officials, the jewel in the South American policy crown. Discussing Colombia, Pentagon spokesperson James Gregory once described the ‘counter-narcotics’ policies there as among the US government’s “most successful and cost-effective programs”, adding that, “By any reasonable assessment, the U.S. has received ample strategic national security benefits in return for its investments in this area.” With the correct understanding of national security in mind the comment is no doubt correct: Colombia remains Washington’s last bastion in a region increasingly asserting its independence, and is committed to the desired economic policies, those that preference foreign capital over local needs. If even the most minimal investigation is carried out it is the analyses that are “lunacy”. The policies make sense, given the objectives and the values.

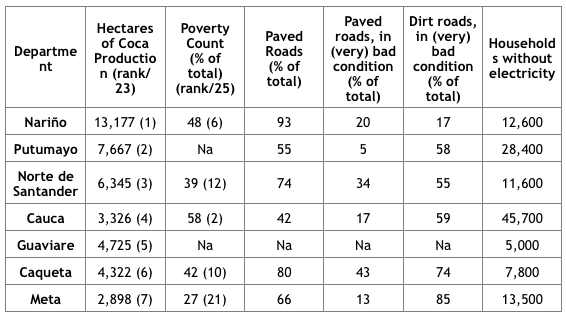

Attacking the Problematic Poor

Fumigation’s longevity in Colombia is not just a reflection of goals being achieved, but of the nature of the Colombian state and its attitude towards the rural poor. Rural communities, on the blunt end of the state’s economic policies for decades, are a thorn in the side of the Colombian government. Those who decide to grow coca are particularly hated. They are not the invisible poor, they are the problematic poor: they don’t just ask for things like schools, hospitals, paved roads, and markets for their products, they take matters into their own hands: they have the gall to cultivate a durable crop with a stable market in order to feed their children. Were these impoverished families to behave as the Colombian state wants them to – abandon their land, relocate to the luxury of the urban slums, or perhaps seek work with a monoculture enterprise – the matter could be amicably and peaceably resolved. As things stand, it has been beholden on Bogota and Washington to attack them with chemical weapons until the lesson is properly absorbed. The slums rimming the major cities are a testimony to the success of the dual chemical-paramilitary attack.

The persistence of fumigation also demonstrates the utility of hiring private contractors to carry out criminal state policies. With limits imposed by the US Congress on the number of military personnel allowed in-country, DynCorp has carved out a role as a significant actor in Colombia’s civil war: employees pilot fumigation and observation planes and helicopter gunships, take part in search and rescue operations, train local forces, and maintain vital materiel. Were US military personnel behind the controls, the Colombian civil war could technically be considered internationalised, and International Humanitarian Law would be applicable. Given the nature of DynCorp’s role and the effects of fumigation, there are suggestions they could be acting in violation of IHL, but agreements between the Colombian and US governments have granted impunity to foreign military forces and contractors alike.

It is useful then that DynCorp’s operations are for all intents and purposes clandestine, akin to employing local paramilitary groups: contractors are accountable to no-one, protected from prosecution, and expendable. “If a [contractor] is shot wearing blue jeans,” remarked one PMSC lobbyist, “it’s page fifty-three of their hometown newspaper.” In an illustrative case back in 2003, a court in the Colombian department of Cudinamarca, responding to complaints brought by victims of fumigation, ordered the policy be stopped pending tests of the chemical being sprayed. The decision was overturned by an appellate court, which ruled that “Colombia should be able to defend itself against the guerillas and paramilitaries,” in the words of a legal analysis published by the Open Society Foundations. The appellate court “took the view that the state was entitled to continue its actions because the growth of coca plants was a threat to state security.” The decision has obvious implications for claims that DynCorp is doing counter-narcotics work in Colombia.

In order to carry out a policy that is damaging to people and the environment and a possible violation of IHL it makes sense to outsource operations to individuals who can act above the law and below the radar. From the War on Drugs to the War on Terror, policy makers are fully cognisant of the value of outsourcing. The US and the UK, the primary employers, have refused to sign UN conventions which could theoretically limit the use of mercenaries in international affairs. Instead, the post-2001 bonanza for private contractors is continuing a pace: the Pentagon recently announced it would be soliciting applications for a $3 billion contract to undertake ‘counter-narcotics’ and ‘counter-terror’ operations across the globe.

For the US government, “counter-narcotics” has always provided provided a reliable, convenient and flexible euphemism – for militarisation, repression, social control, counter-insurgency. And so it makes sense that, when responding to criticisms that DynCorp employees in Colombia were no more than mercenaries, a US State Department official should resort to the well-worn explanation: “Mercenaries are used in war,” he replied. “This is counter-narcotics.”

See also The Chemicals Don’t Discriminate, Le Monde Diplomatique

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in Vienna will decide next week between two opposite proposals by China and the WHO about international control of

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in Vienna will decide next week between two opposite proposals by China and the WHO about international control of The 58th Session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in March 2015 has been asked to consider a Chinese proposal to place

The 58th Session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in March 2015 has been asked to consider a Chinese proposal to place