Ross Eventon*

In 2011, when the multi-billion-dollar Plan Colombia had officially come to an end, the UNDP described the “rural development model” in Colombia as “highly inequitable and exclusionary.” The model “causes innumerable rural conflicts, does not recognize the differences between social actors, and leads to the inappropriate use and destruction of natural resources.” Any attempt to improve the situation, the UNDP argued, must be based on changes to “structural factors”, among which were “the concentration of rural property, poverty and misery, and an unjust and exclusive social and political order.” A year later a Free Trade Agreement with the United States came into effect, and the incomes of hundreds of thousands of farmers fell as subsidised foreign goods entered the local market. This coincided with an economic slowdown, and GDP growth fell steadily from 6.9% in 2011 to 1.4% in 2017, the year coca cultivation reached record levels. Over roughly the same period, global drug use is considered to have risen by 30%. Today around half of Colombians work in the informal sector. In the countryside, where one in three people are classified as poor, this figure may reach 85 %. The economy revolves around extractive industries, mono-crop agriculture and financial services, a combination that concentrates wealth and cannot provide stable employment for a large segment of the population. In a country rich in natural resources the level of inequality is comparable to resource-starved Haiti, the poorest country in the hemisphere. Land concentration, the historic grievance of the insurgent movements, is today the most unequal in Latin America.

These are the structural factors to be kept in mind when we discuss the country’s many problems. To claim in this context that a rise or fall in the amount of coca being cultivated is a ‘success’ or a ‘failure’ is a false economy. For hundreds of thousands of people coca is an important cash crop, and a reduction in cultivation levels means a reduction in their income. It could also imply a technological improvement and better productivity. In an environment where demand is fixed, reductions in cultivation may ultimately lead to a rise in prices and an even greater incentive to cultivate. It would be difficult to classify any of these outcomes as a ‘success’. A genuine success would be led, first and foremost, by the movement of large numbers of people into the formal sector, either through job creation or subsidised agriculture. The reduction in cultivation would then be a consequence of this structural change.

For American and Colombian policy makers, who are both committed to the economic status quo, the question is how to reduce cultivation without changing the structural factors. This is a difficult problem and no one has yet found an answer. In December, President Ivan Duque announced the government would in 2021 resume aerial fumigation of coca crops with glyphosate. This policy, of which Colombia was one of the world’s few practitioners, ended in 2015 when the WHO stated the popular weed killer could be carcinogenic in humans.

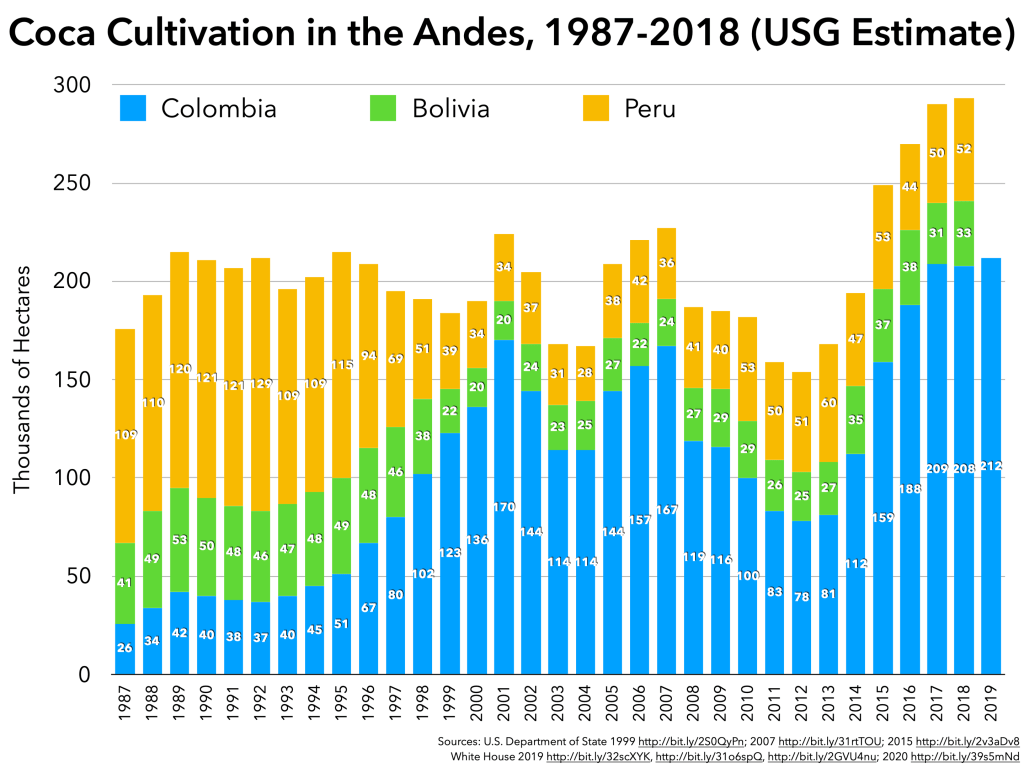

The damaging environmental and health effects of aerial fumigation are well documented. In the past it has led to protests and violent repression. It also doesn’t work: through the 1990s cultivation rose along with fumigation; in the early 2000s cultivation levels decreased slightly as fumigation continued, although exports of cocaine increased; and between 2007 and 2012, while aerial fumigation decreased sharply, the hectares under cultivation was reduced by half. If we search for alternatives, Bolivia provides an example of what could be achieved with investment, decriminalisation and a recognition of the farmers’ plight.

Yet all of this is considered irrelevant. The decision to use aerial fumigation must, therefore, be based on other considerations. Cost is clearly not one of them: it has reached such a point that analysts in Colombia claim it would now be cheaper to purchase the entire coca crop than to undertake a year of counter-narcotics operations. The human suffering and the environmental damage are also not considered relevant, neither is the woeful efficacy of the policy, which is today rejected everywhere else in the world for good reason.

Colombian President Ivan Duque, announcing the return of fumigation, said less coca was cultivated in 2014 than in 2000, and for this reason aerial spraying was necessary. It is unlikely Duque himself could be convinced by this. (It could just as easily be argued that, because cultivation and fumigation both increased in the 1990s, fumigation caused coca cultivation). Duque described aerial fumigation as part of a “tool kit” of policies. Among them was Alternative Development, which tries to help farmers to switch to cultivating legal crops. Such initiatives generally meet the same fate in Colombia: they are under-funded and branded failures. Every journalist who makes the journey to coca growing regions reports hearing from farmers the same tired lament: the government promises much and delivers very little. Meanwhile, aerial fumigation, which is expensive and requires the participation of the military, does receive the necessary funds. This gives some sense of whether reducing cultivation in a sustainable way is a genuine aim of government policy.

If fumigation fails by the standard measures, what does it do well? At the very least, it creates the impression, primarily in the United States, that a major strategic ally is ‘doing something’ to try and reduce coca cultivation. For a long time it also ensured cooperation between the US and Colombian military and granted the US, via private contractors, a covert entry-point into the civil war. Today, we do not know whether the United States is, behind the scenes, predicating further aid on the re-adoption of spraying.

Aerial fumigation has also proven an effective means of displacing people. When coca was being grown in areas controlled by the guerrilla, destroying the plant was a thinly concealed attempt to undermine their finances and, in counter-insurgency jargon, to ‘drain the sea’. After its experience in Colombia, Washington had similarly proposed aerial fumigation be used in Afghanistan, as part of a counter-narcotics initiative very openly aimed at the finances of the insurgency, but the policy was rejected by the Afghan government.

How sincere is the Colombian government’s concern with coca cultivation? The past record suggests counter-narcotics policies have been a tool used to achieve other objectives, rather than to decrease the needs or incentives that lead people to break the law. The same can be said of Washington, which pushes the onus onto supplier countries, when the real issue is the demand coming from the US for an illicit product. As Colombia turns again to fumigation, we can expect a tirade of analyses that criticise this ineffective and costly policy. But for the Colombian and American governments, their past experience with fumigation has convinced them it should be used again. The harmful, criminal policy is, in their eyes, achieving something close to success.

*GDPO Research Associate